When we think about the cold war and the eastern bloc, one thing we often think of are the defectors. It’s sort of the ultimate proof that things in the east were bad, right? If someone is willing to risk their life to cross a heavily guarded border to the west, well surely the east was nothing more than a prison, right? Well to those people it certainly must have been. I’m not going to downplay anyone’s personal struggle and indeed, a great many suffered horribly. But let’s not pretend that this was a one-way street. Just as there were eastern defectors, there were western defectors too. Let’s talk about some of them.

Before the Great Depression

It should be understood that the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 was actually immensely popular for many people all over the world. Workers movements in Europe, America and elsewhere had been theorizing socialism for decades but never knew if they might actually see it. When the revolution was almost immediately hit by a coalition invasion to crush it, what many saw was a potential workers utopia being strangled in its infancy. They knew conditions were brutal and that the region was war-torn, but the potential was there. Nobody had any conception of the internal violence that came later.

The earliest hint of defectors to the Soviet Union was likely seen in the founding of the Society for Technical Aid to Soviet Russia, founded in May 1919 in New York, USA. This society expanded rapidly across the USA and Canada, getting particular support among anti-Tsarist Russian emigres who wanted to return to their homeland and help rebuild. Before April 1921, around 16,000 Americans are believed to have arrived in the USSR. Many of these had arrived independently, but as of April, any migrants were required to come as part of an official foreign commune.

Between the end of 1921 and October 1922, the society was directly responsible for seven agricultural communes, two construction communes and one mining commune in the USSR. The experts brought with them vast amounts of seeds and equipment to do their jobs, a value estimated at around $500,000. Not exactly insignificant, especially at that time. The subsequent years saw this number expand.

By 1923, with the civil war largely over and Soviet authority secured, the society had expanded to include over 75 branches with 20,000 members. At this time, most of those traveling to the USSR to work were doing so for ideological purposes or to reunite with their families. The number of western defectors was still quite low, with Russian emigres making up the majority of those who traveled, while many more were simply going for a period of a year or two to work before returning back home.

Kuzbass Autonomous Industrial Colony

One of the most notable examples of western defectors at this early times was seen in the Kuzbass Autonomous Industrial Colony. The roots of this colony could be found in a letter Lenin sent, directly appealing to American workers for aid. America was, after all, probably the most technologically advanced state in the world by this point. He was met by Sebald Rutgers and Bill Haywood, prominent American socialists and trade unionists who agreed to help in the establishment of a colony in Kuzbass to aid in the desperately needed restoration of industry there.

In March of 1921, the first public call was made in various communist papers for potential western defectors to aid in the establishment of this colony. Unlike others which particularly sought to appeal to Russian emigres, the Kuzbass commune was pushed as a demonstration of socialist ideology for all Americans to take part in. On the 25th of December, an agreement was signed which gave the American colonists a mine, a construction plant and 10,000 hectares of agricultural land. The colonists pledged to stay for at least two years and obey Soviet law, but otherwise were free to organize themselves as they wished.

Ultimately at the start of 1923, around 750 people arrived from a variety of nations, with Americans at the forefront. A further 5,000 Russian miners worked on the colony to keep its productivity high, increasing to a total of around 8,000 by the end of 1923. The ‘western defectors’ included a surprisingly large number of women for the time, enticed by promises of gender equality largely unheard of in the rest of the world. American colonist Ruth Kennell wrote very sympathetically about life on the commune, praising the level of women’s rights and the decent (yet basic) living conditions, though some others were a fair bit more skeptical.

In 1926, Sebald Rutgers vacated his position as head of the commune and was replaced by a Russian engineer who proved much less popular. The foreigners and Russians each believed the other was given preferential treatment, with further divisions arising between the labourers and white collar workers. What spelled the death knell for the colony was the institution of Lenin’s ‘New Economic Policy’ which replaced the communal living situation with standard wage-labour. This further divided residents and made the more committed communists return home in protest, feeling they’d been scammed. On December 28th, 1926, the colony was disbanded. Most returned home, though some moved to work elsewhere in the USSR… Still more faced repression.

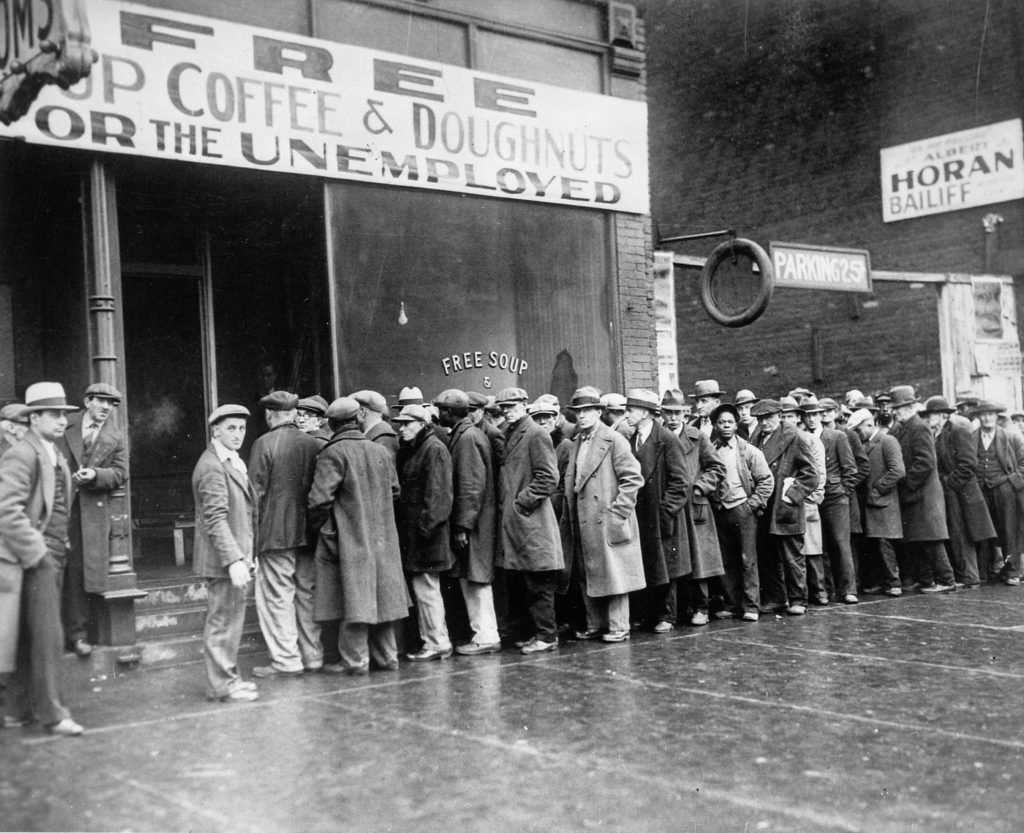

The Great Depression

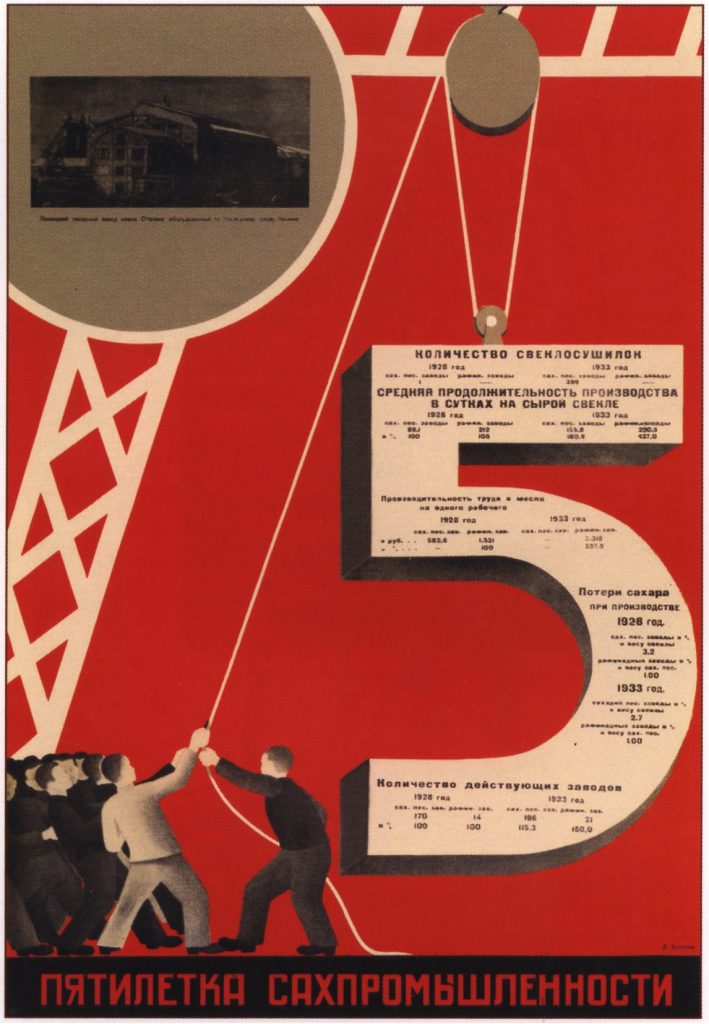

Towards the end of 1929, America suffered an enormous economic crash and entered the Great Depression, with much of the capitalist world following after it. Jobs became scarce and many became desperate, unable to make a living for themselves or their families. For these potential western defectors, what they needed as an alternative… And sure enough, the Soviet Union had begun its first five year plan in 1928, standing outside of the capitalist system and thus unaffected by this economic downturn, the Soviet Union was instead experiencing a labour boom. It was said that one could come to Moscow from any profession and have a job within a week.

The appeal was enormous and in contrast to the earlier migrants ideological convictions, many moved to the USSR to find work. The Sixteenth Party Congress of 1930 in the USSR led to an agreement to seek at least forty thousand foreign skilled workers to aid in the success of the five year plan. Reportedly in the first eight months of 1931, a hundred thousand applications were sent from America, with ten thousand being accepted. Still more arrived as tourists and sought out work when they arrived. Pretty stark contrast to the idea of the USSR as an impoverished hellscape, at least at this time, Russia had become a land of opportunity.

By September of 1932, it’s believed there were 9,190 foreign specialists and 10,655 foreign workers in the USSR from a variety of countries. Counting their families, the total number was 17,655. Aside from Americans, over 10,000 Finnish people are believed to have crossed into the USSR both legally and illegally over the course of the 1930s, with yet more coming from neighboring Poland. Alongside the harsh economic impact of the great depression, many were also fleeing from the rising tides of fascism in other parts of Europe, particularly communists who felt at danger anywhere else.

The End of Western Defectors

This tide of western defectors ultimately didn’t last too long. Towards the mid-30s, the great depression was coming to an end. Opportunities reappeared in people’s home countries and many wished to return home and resume the lives they left behind. Thousands began migrating back, though more still found they actually weren’t able to. Some had apparently had their passports revoked upon moving to the USSR and with the political climate becoming increasingly tense, the desire to get home became desperate.

Americans in particular rushed to the American embassy in Moscow and were largely turned away. Though with their presence at the embassy noted, many of these Americans were arrested by the NKVD, brought in for interrogation and either sent to gulag’s or in some cases, outright executed. Stalin’s great purge saw the end to most of these western defectors, as it became popularly considered too dangerous to travel and live in the USSR. Even when the purge had ended, the stigma stayed, with the carnage of WW2 providing the final nail in the coffin for many as Europe and America’s economy permanently surpassed the Soviets and the cold war began.

Now, there were certainly more western defectors after this. Not just to the USSR, but to other socialist countries as well! But nothing ever occurred on the same scale and I would say that everything afterwards is perhaps more deserving of its own article later down the line. As it stands, this particular chapter of history is swept under the rug in most countries. It’s perhaps more desireable to think of the USSR as an awful hellscape that nobody ever wanted to visit, rather than a new economic experiment that gave many opportunities, made many disillusioned and put quite a number more in early graves. Like many things, the truth is really rather complex.

Among those who immigrated in this time, there’s a few notable cases you should check out! The earlier mentioned Ruth Kennell wrote extensively about her time in the American commune, while famous American actor and singer Paul Robeson traveled to the USSR just before the great depression and declared “Here I am not a Negro but a human being for the first time in my life… I walk in full human dignity.” In 1936, he then sent his son to live and study in the USSR for a time. Lastly, black American Marxist Harry Haywood lived and studied in the USSR from 1925 to 1930, returning with a highly influential book of his experiences called ‘Black Bolshevik: Autobiography of an Afro-American Marxist.’