1972, Dirs. Choe Ik Gyu and Pak Hak

With little sister, Sun Hui, who got blind by the cruelty of the landlady, Kkotpun sells flowers to pay for the medicine of her mother who has fallen sick from slavery as landlord Pae’s servant. In spite of her devotion, her mother dies and Kkotpun sets out on a long journey to see her brother, who was unjustly thrown into prison years before. When she hears of her brothers death from a jailor, she attempts her own life, but thinking of her blind sister, she comes back home. Hearing her sister was lured away by the landlord, she protests against the landlord. But she is severely beaten and locked in a store. On the other hand, her brother Chol Ryong who joined the Korean Revolutionary Army after his escape from the prison, stops over at a mountain hut near the village. There he finds Sun Hui who was was rescued from death by the owner of the hut. He encourages the villagers to finish off the landlord and his minions and saves his sister Kkotpun. Kkotpun follows her brother to join the antiJapanese revolutionary struggle led by Kim Il Sung.

The Flower Girl is by far the most famous North Korean Film and regarded by the state as an Immortal Classic. The film is based on the “revolutionary opera,” allegedly written by Kim Il Sung when he was imprisoned by the Japanese for his revolutionary activities. In Kim Il Sung’s memoirs, With the Century, he noted that the play was first performed by Koreans in Jilin province on the 13th anniversary of the October Revolution. And, according to official lore, the play was not performed until it was “improved and adapted for film, and re-written as a novel under the guidance of” Kim Jong Il.

The film is the quintessential example, as pure a propaganda film as one could hope to see. Production began in April, 1972, and the film was co-directed by Choe Ik Gyu and Pak Hak. Choe had been entrusted by Kim Jong Il with the 1968 film adaptation of another Immortal Classic and revolutionary opera, Sea of Blood. Pak Hak, had starred in 1953’s Scouts, a war film shot during the Korean War, and would go on to direct 1974’s The Fate of Kum Hui and Un Hui.

The film was shot almost entirely on studio sets and a impressively convincing backlot dressed as Korea under Japanese occupation. The film follows a penniless flower girl who has her spirit stomped time and again by the cartoonishly malevolent Japanese, who let her family rot to death under the weight of extreme poverty. The film is a steady descent into unending pity, until her brother (representing Kim Il Sung’s invincible and noble Revolutionary Army) appears on the scene to overthrow the landlord at the center of her misery.

What’s interesting about The Flower Girl, and the many North Korean films produced in this style, is the almost total absence of the formal flourishes that the European and American films had introduced to the medium by the 1970s following the French New Wave. There is little in the way of style or embellishment to underscore dramatic beats, giving the film a straightforward, workmanship quality. The blocking of actors is staged with an artificial rigidity, often leaving key faces out of view at moments where Western audiences are accustomed to expect a reverse shot or close up. Many scenes are shot in a artlessly framed wide and stay there, regardless of the dramatic value of what is being said.

Nevertheless, the film has several worthwhile images with an undeniable gauzy and ethereal quality, used to especially flattering effect in the opening as our protagonist gathers flowers to sell on the streets once the market opens. At its most attractive moments, the film feels as if it were released closer to the period it portrays, looking more like a product of the early technicolor days of Hollywood instead of the 1970s. Artistic direction aside, this is likely the product of older, outmoded lenses and equipment used, as well as the filmmakers holding tightly to a rudimentary emulation of Western and Soviet films they admired without understanding the visual logic underpinning them.

One could watch The Flower Girl and wonder if the filmmakers know the power of a close up, or what, if anything, a creeping camera move communicates to the subconscious of the audience – or if they just see these choices as interchangeable units of communication, each as effective as any other.

Unlike Western cinema which had been sharpened for decades under a traditional studio system and had begun to break free of those traditions into experimental pop territory by the 1960s, The Flower Girl represents a much earlier step in a nation’s love affair with the movie camera.

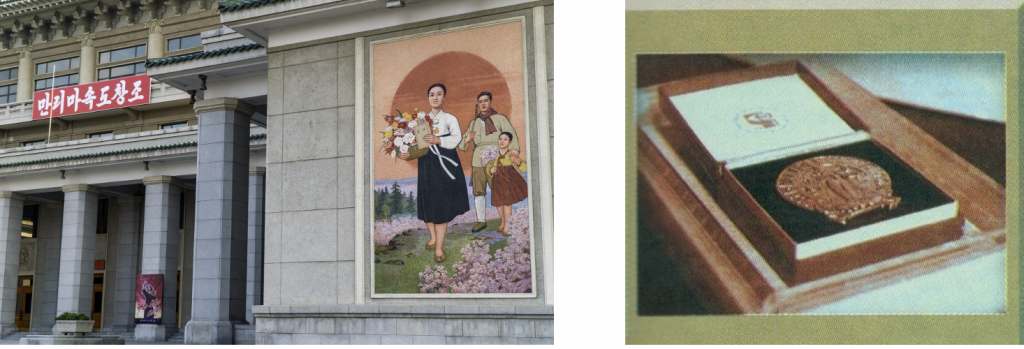

The Flower Girl played at a number of Eastern Bloc festivals and became the first international award-winning North Korean film when it won a Jury Prize at the 1972 Karlovy International Film Festival in Czechoslovakia. The film’s international recognition must have lead to a boastful article in a 1974 Korean Review which claimed: “In recent years our film art has created an unprecedented sensation in the world’s filmdom… The revolutionary people of the world are unstinting in their praise of this feature film and other monumental works, calling them ‘the first-class films by international standards’, ‘the most wonderful movies ever produced’ and ‘immortal revolutionary and popular films’.”

The movie was also released in China at the outset of the Cultural Revolution. It was apparently so popular that some Chinese cinemas introduced 24 hour programming for the movie. One North Korean guide told me that Chinese tourists still ask about the film. In 2009, actress Hong Yong Hee, who portrayed Kkotpun, received Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao when he arrived on a state visit to the DPRK.

Images of Kkot Bun can be found sprinkled throughout North Korean culture, most notably on the one Won note (no longer in circulation following several rounds of currency reforms) as well as on a huge mural at the entrance of the Pyongyang Grand Theatre. According to North Korea state media, the play has been performed over 1,400 times in 40 countries. In South Korea, the film was banned as communist propaganda until 1998.

Watch The Flower Girl online for free with English subtitles HERE.